Meningitis outbreak in Democratic Republic of Congo highlight the need for local capacity building

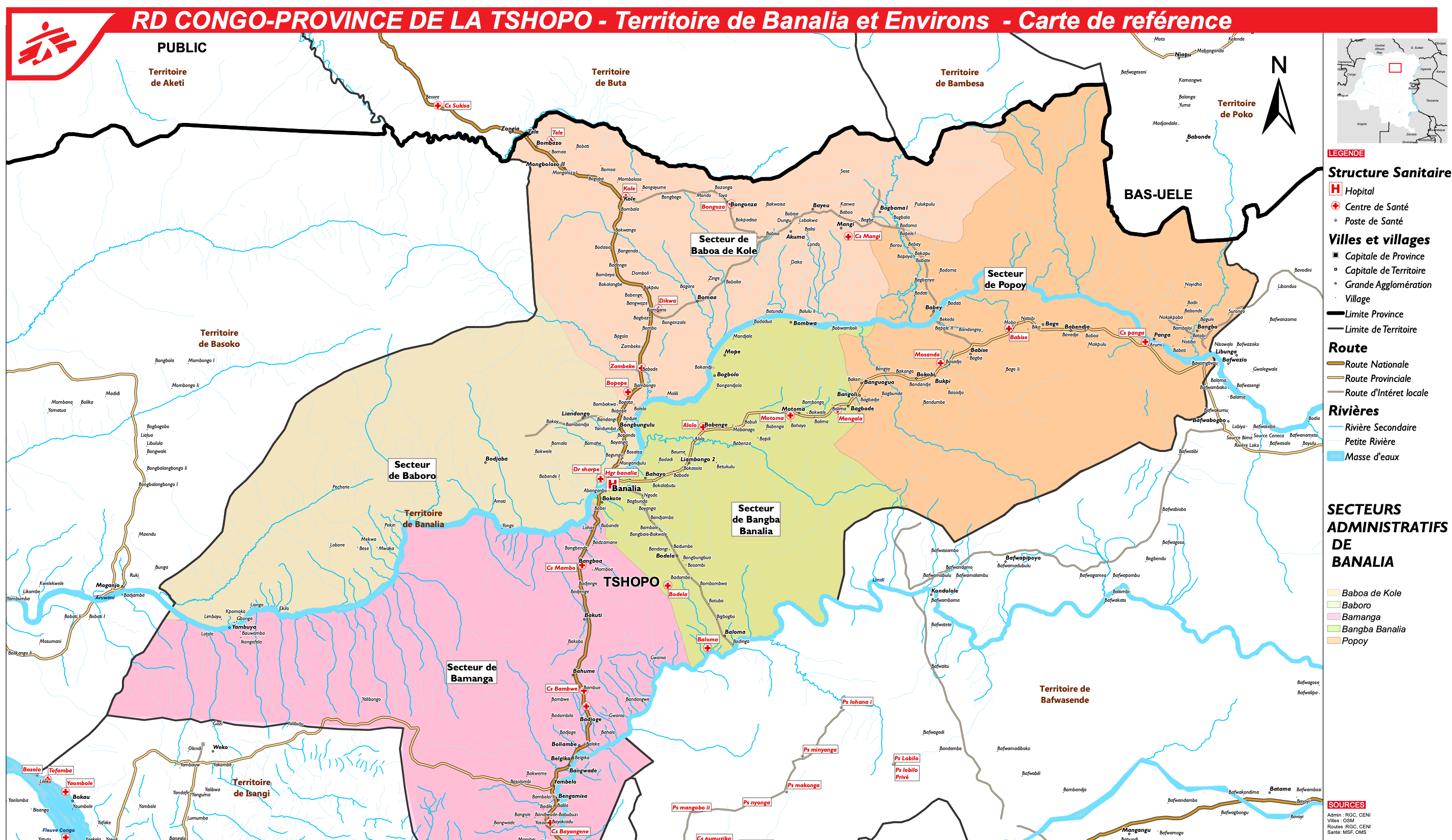

Credit image : Médécins Sans Frontières (MSF)

On September 8th 2021, the Democratic Republic of Congo declared a deadly outbreak of meningitis among miners in the Health Zone of Banalia, TSHOPO province, located in the north-east of the country. This lies within the African meningitis belt prone to unpredictable meningitis epidemics (WHO Africa). As of the 19th October, a total of 2187 suspected cases and 199 deaths (9% case-fatality) have been reported (WHO Africa).

These tragic events raise important issues that need to be addressed if African countries are to win the fight against meningitis as outlined in the WHO roadmap to defeating meningitis by 2030.

The first is the need to build in-country laboratory capacity capable of supporting a rapid and accurate diagnosis of bacterial meningitis. Despite the presence of many meningitis epidemic risk factors, such as the overcrowded living conditions of the miners and the region being part of the meningitis belt, as well as the characteristic clinical manifestation of high death rate, fever and stiff neck, surprisingly meningitis was not the primary consideration. Instead, samples were collected to test for Ebola virus disease, shigellosis and salmonellosis at (WHO Disease outbreak news) the National Institute for Biomedical Research (INRB) laboratory in Kinshasa. When meningitis was finally suspected, the National laboratory was incapable of detecting Neisseria meningitidis and samples were shipped to France, where the Institut Pasteur in Paris confirmed the serogroup W Neisseria meningitidis epidemic. The lack of local capacity is likely due to lack of reagents, experience and/or training as opposed to a lack of equipment, since similar molecular techniques are used to detect Ebola. This has caused a tragic delay of three months in confirming the outbreak. Rapid diagnosis and treatment of meningitis are crucial for appropriate case management and for containing the outbreak; shipping samples to another country is not only slow and inefficient, but counterproductive when the goal is to build local laboratory capacity.

The second issue is the urgent need for an affordable vaccine offering protection against multiple meningococcal serogroups. The pentavalent (ACWXY) NmCV-5 conjugate is produced in the same facility as MenAfriVac and is well-advanced in clinical development. Plans must be made now for its widespread implementation. Following the success of MenAfriVac, the monovalent conjugate vaccine against serogroup A disease, a level of complacency has arisen regarding meningitis epidemics in many African countries. Serogroup W meningococcal disease can present with atypical symptoms including abdominal pain and diarrhoea. People may not be aware that MenAfriVac only protects against disease caused by serogoup A meningococci, and that other serogroups also cause meningococcal disease. They may also have forgotten how unpredictable and stressful these epidemics can be for already stretched public health systems. Reactive vaccination with the currently available polysaccharide vaccines is not the only option for management of outbreaks. As the implementation of MenAfriVac has clearly demonstrated, preventive measures are far more effective, especially when combined with campaigns to educate the population on symptoms and risk factors associated with this disease. Widespread use of multivalent conjugate vaccines will soon be a viable option if funding can be identified.

Finally, this epidemic raises the question of the seasonality of meningococcal disease in Africa, as it started in July outside of the so-called meningitis season. Traditionally, meningitis in the African meningitis belt is expected during the dry season when the Harmattan wind is blowing, usually between November and March depending on the country. A delay in the rains may have contributed to the outbreak in Congo, and with weather patterns becoming increasingly unpredictable with climate change, medical staff must remain alert.

The next epidemics will be unpredictable, and although when and where are questions we cannot answer, it is important that the African public health authorities remain alert to the risk, and ensure they have the laboratory capacity to identify the causative organism rapidly, and respond efficiently to contain the outbreak and save lives.

References